What is insomnia?

Here’s the boring answer. From a diagnostic perspective, insomnia has four main components:

- Trouble falling asleep or staying asleep.

- Sleep disturbances are accompanied by daytime symptoms such as sleepiness, fatigue, or irritability.

- These symptoms occur despite adequate opportunities and circumstances for sleep. (In other words, you can’t sleep well even though you have a safe, quiet place to sleep, enough time to sleep, and you’re trying your best to sleep.)

- Sleep sucks 3 or more times each week.

Here’s the longer, more interesting answer:

Many people think that sleep is merely the absence of wakefulness—just like darkness is the absence of light. You might have pictured wakefulness like a dimmer switch: you become more alert when you turn it up, and you fall asleep when you turn it down. On the surface, this doesn’t sound like a bad model, but it doesn’t explain how your body actually works.

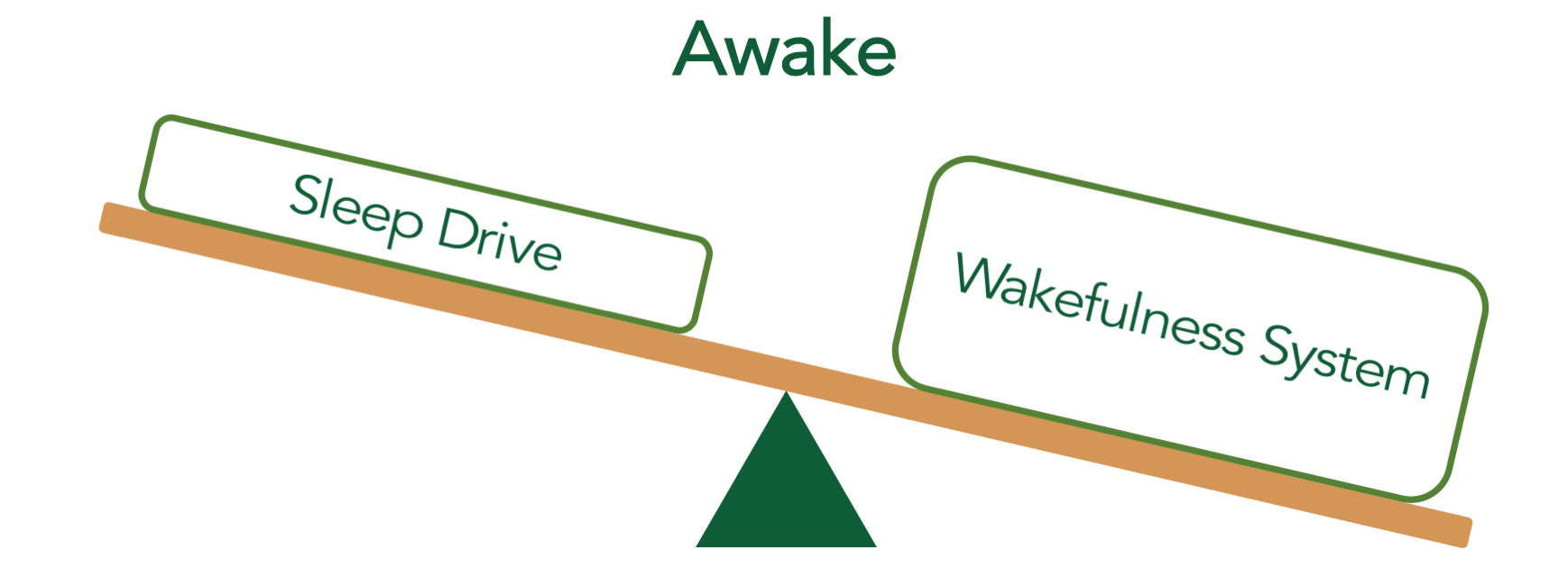

Scientific models describe sleep and wakefulness as opposing, active processes. This is often compared to a seesaw. When your wakefulness system is more active than your sleep drive, you stay awake.

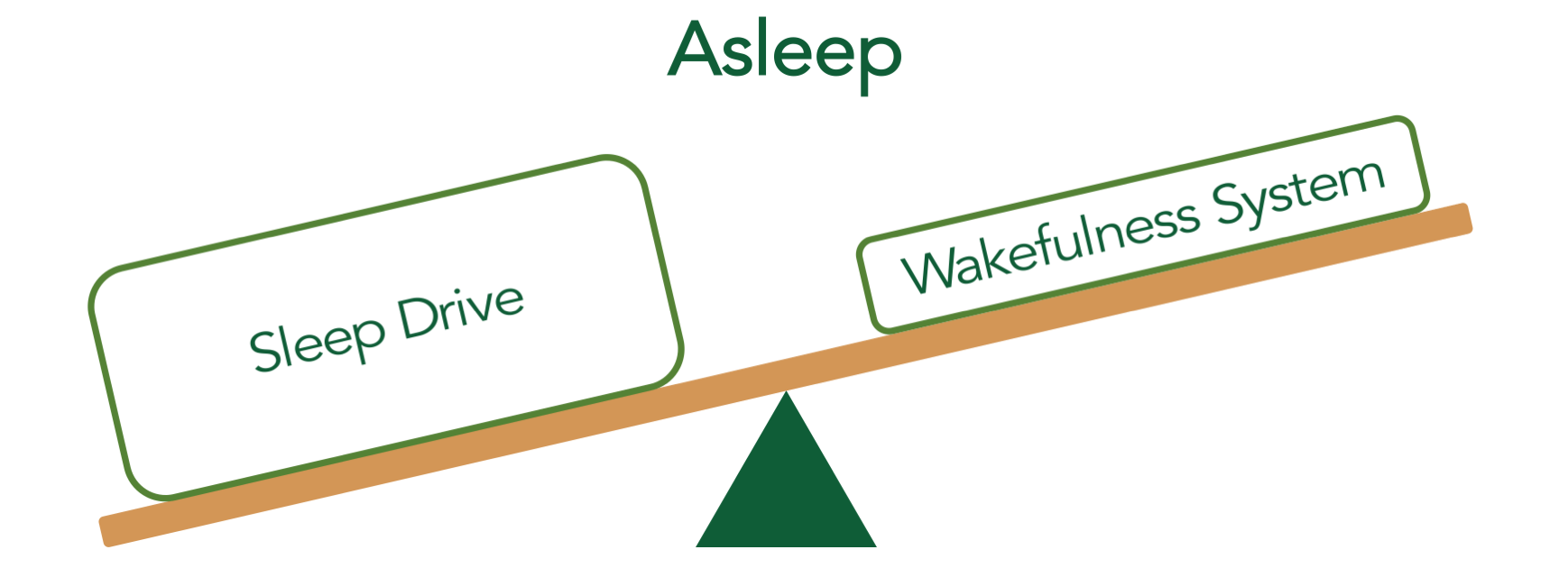

In like manner, sleep happens when your sleep drive becomes significantly more active than your wakefulness system.

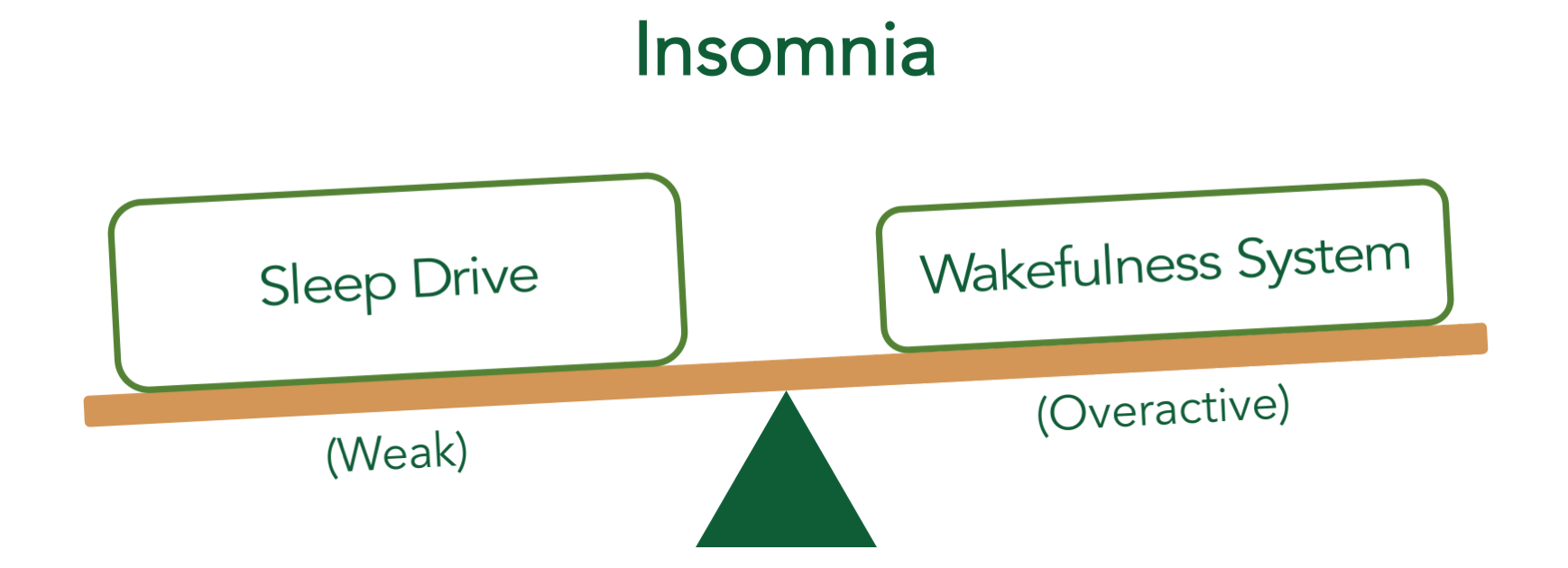

This models suggests two possible causes of insomnia: an overactive wakefulness system and a weak sleep drive. Experimental evidence supports both mechanisms, but an overactive wakefulness system—a phenomenon known as hyperarousal—turns out to be the primary driver of insomnia.

Hyperarousal explains why you feel dead tired and wide awake at the same time. Your body has a brick on the gas pedal, and pushing the breaks isn’t enough to calm down the car!

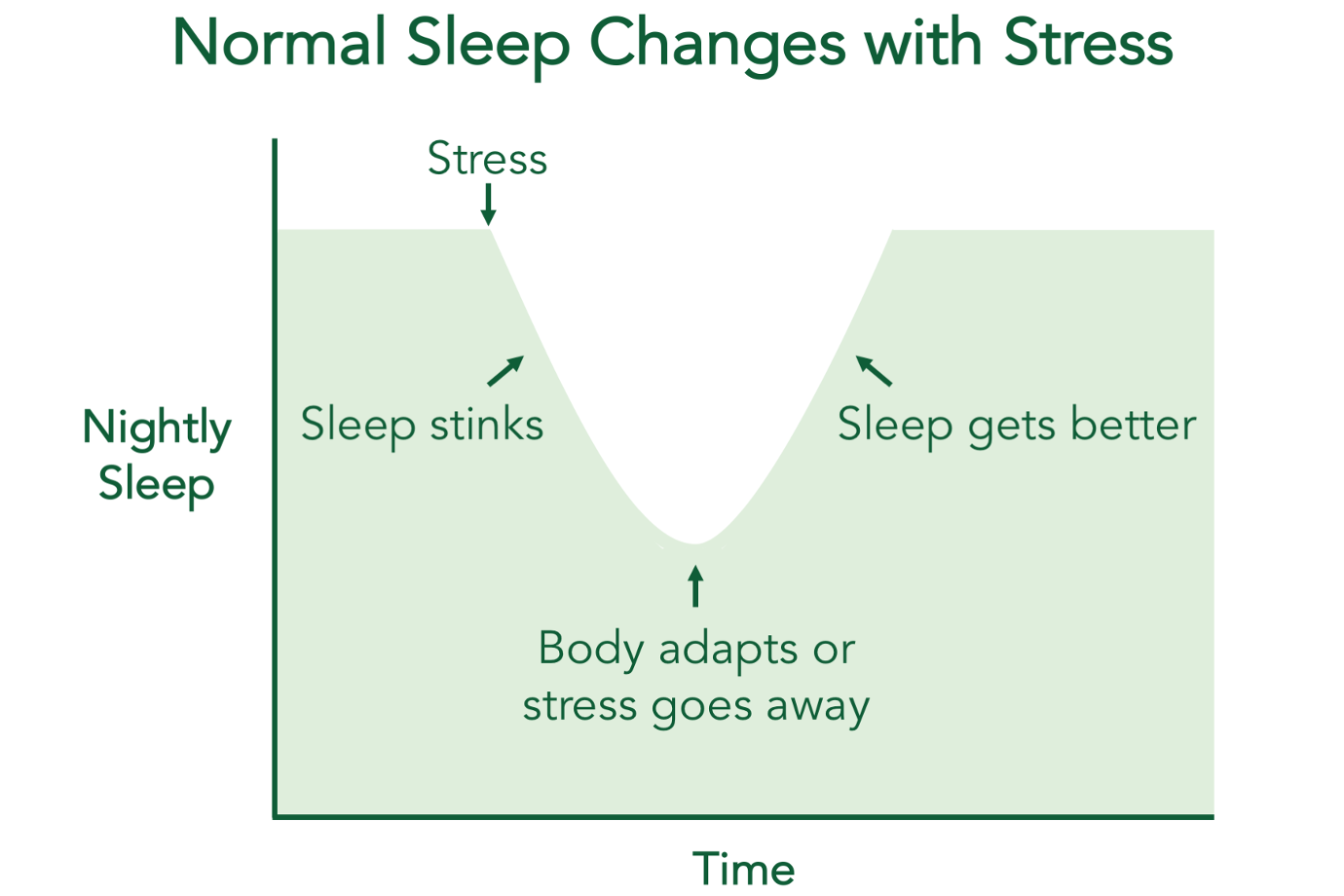

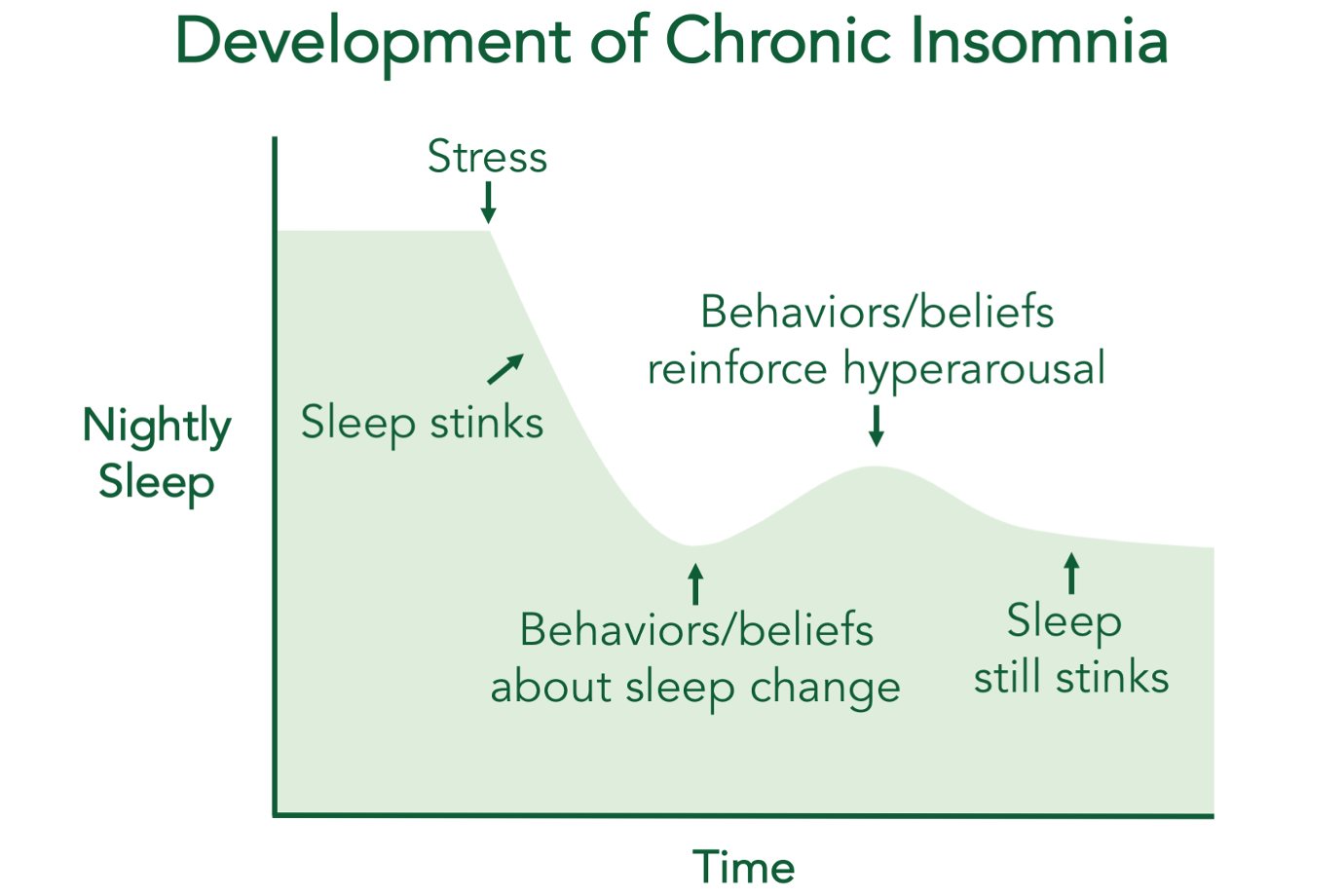

Hyperarousal is part of your body’s natural response to stress. Many people can’t sleep before an important test, a big interview, or the start of a new job.

Thankfully, sleep usually improves when a threat goes away. But in people with insomnia, sleep disturbances persist even after the resolution of an acute stressor. How can this be?

Now to be completely honest, we don’t know everything there is to know about the persistence of hyperarousal. We have neuroanatomical, chemical, electrical, and genetic models of your wakefulness system and sleep drive that can in part explain who develops insomnia. But our most important insights about insomnia have come from behavioral models that explain why hyperarousal persists.

In other words, there is no reason to believe that your sleep system is irreparably broken. This is great news! Insomnia is generally not the result of a major genetic disorder or a purely chemical imbalance. For that reason, medication-based treatments might provide a short-term fix, but they don’t address the underlying cause of persistent hyperarousal. (I’m not against medication—I’m a psychiatrist, for heaven’s sake. I just don’t believe that medications should be the first-line treatment for insomnia.)

There are three specific reversible changes that typically happen to people who develop insomnia. First, people typically change their behavior in response to sleep disturbances. You might have started sleeping in on weekends, taking more naps, or going to bed earlier. Perhaps you tried taking medications, alcohol, or marijuana to help you sleep. Like many people, you may have increased your caffeine consumption to stay awake during the day.

These behaviors seem to make sense. If you need more sleep, why not give yourself more time in bed and a sleep-inducing medication? How will you get your work done if you’re tired and don’t have that extra cup of coffee? In the moment, these choices seem to help, which is why you might keep doing them. But each of these behaviors has the potential to disrupt your sleep drive and wakefulness system, which ultimately strengthens hyperarousal. As insomnia progresses, you may have learned to rely on these habits more and more, trapping yourself in a vicious cycle of sleep deprivation and insomnia-worsening behaviors.

Second, people with insomnia develop unhealthy thoughts and beliefs about sleep. You probably spend a lot of time thinking about sleep—which is a perfectly natural response to insomnia. A sleepless night stinks under the best of circumstances. When you haven’t consistently slept well for months or years, every moment of sleep feels critical. It’s hard not to develop negative thoughts and beliefs when you’re suffering like this. Often, the act of worrying about sleep becomes a brand-new stressor that contributes to hyperarousal. And unless sleep actually improves, this stressor doesn’t go away.

Finally, lying awake in bed teaches your body to associate your bedroom with wakefulness, rather than sleep. This is a phenomenon known as a conditioned response,and it results in strong physiological changes that make falling asleep much more difficult. This means that insomnia isn’t all in your head; there are distinct, biological processes that keep you awake at night.

Jeff Clark, MD

Who is the camp director?

P.S. This model is also the basis for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)—a treatment that reverses insomnia in 3 out of 4 people. If you’d like to learn more, I encourage you to try Slumber Camp, a 28-day CBT-I course designed to help you sleep better without medications. It’s just $29, and it comes with a no-questions-asked, 100% money-back guarantee. (I also offer need-based scholarships that allow you to pay what you can, even if you can’t pay at all.)

I hope you’ll give it a try!

Copyright 2017 - , Wonderberry LLC (dba Slumber Camp).

Slumber Camp teaches the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), an evidence-based therapy. It is not intended to replace the diagnosis, advice, and treatment provided by a qualified healthcare professional. Slumber Camp is not for everyone, and you should talk with your doctor to consider your individual situation before making any health-related decisions. Slumber Camp cannot be held responsible for any harm caused by your choice to engage in this course. By using this website, you agree to be bound by the terms of our Legal Agreement.